I must admit, I am drawn to Byzantium, to the ancient cities and culture of Eastern Christianity. In some circles it is common to describe anything useless or helplessly complex as “Byzantine”. This is just as preposterous as the French thinkers calling themselves the promoters of the Enlightenment in contrast to those thoughtful theologians and philosophers from the supposed “Dark Ages” upon whose shoulders they stood.

Eastern Christianity often suffers at the hands of Western ignorance. Many people summarize Eastern Christianity as Roman Catholicism without a pope. The truth is, Eastern Christianity is a fount of theology, spirituality, art, and music that comes to our aid in these pressing times.

In our liquid modernity and postmodern churches, we do not have two feet to stand on. We act as if every institution and church tradition must be undone in order to be free. However, the faithful witness of Christians in the East tell us another story. It is not easy to be a Christian today in the post-Christian West yet it has rarely been easy to be a Christian in the East.

While Christians in the West may prefer to seek refuge in the early church and in later Western expressions of Christianity (i.e. the European Reformation), the East today provides traditions and theological undrestandings that can anchor our communities and keep our spiritualities free from self-help, egocentric, consumeristic, and degenerate forms of the Gospel.

May William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Sailing to Byzantium” inspire us to return to the ancient cities of the Orient in order to discover not ruins, but the living faith and tradition of Eastern Christianity and its vibrant spirituality.

Sailing to Byzantium

by William Butler Yeats

I

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees,

— Those dying generations — at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

II

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

III

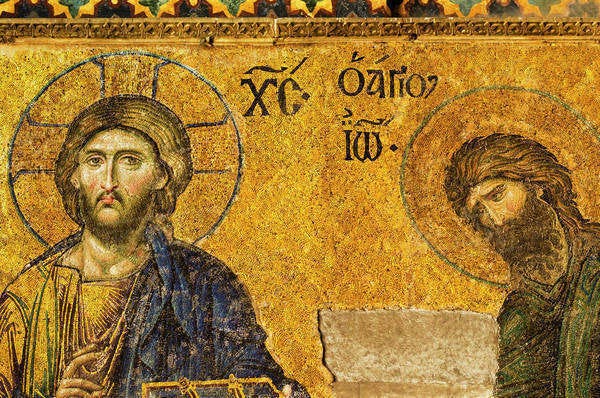

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

IV

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

W. B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium” from The Poems of W. B. Yeats: A New Edition, edited by Richard J. Finneran. Copyright 1933 by Macmillan Publishing Company, renewed © 1961 by Georgie Yeats.